Like a flash of beige lightening, I saw the desert lizard slide over the sandy scrubland. I jumped out of the moving Humvee and started running midair to match the speed. The convoy kept creeping out in front of me as I lumbered into the desert. “What the heck is Lake doing” rang out over the SINGARS radio. My squad leader knew I couldn’t resist engaging with the local Kuwaiti wildlife, especially after seeing a dead on the road monitor lizard a few miles back. This was also evidenced by the copious barracks pets I acquired stateside during our training, leading up to the deployment. From that moment at the Udairi Training Range in Kuwait, I earned the call sign “Critter Getter.” Call signs in the Army served as one part nickname, and more importantly a critical moniker used to disguise our personal identity to the enemy while using our encrypted radio communications.

I wanted to be the bastard child of Steve Irwin and Chris Pontius, one-part wild boy and one-part serious conservationist. I prided myself on having a flair for being an enthusiastic advocate for often maligned wildlife. I carried a small retractable snake hook and camcorder on just about every mission while in Kuwait and Iraq. Even though I shot more videos than photos, my cameras were constantly aimed in the direction of wildlife. Between missions, or on downtime in far flung places, I would poke around the various bases in search of Middle Eastern wildlife.

Everything was new to me, and it was amazing!

Once, we turned my wall locker into a battle dome for a recently captured Kuwaiti hedgehog so that it could devour camel spiders and beetles. It was amazing to watch that spikey little mammal devour insects and other invertebrates. Having only seen them in captivity prior to finding them in the wild, I had no idea they were such voracious predators. While we were still in training, I acquired an ant farm and stocked it full of local ants. I kept the gel enclosure full of fire ants next to my bunk until one of my superiors saw those spicy formicans and disagreed with their internment. Leaving no debris unturned, I found all matter of wildlife in that foreign soil from scorpions to lizards and everything in between.

One afternoon in Kuwait between missions, my best friend and I decided to go flip rocks and chunks of concrete around the HESCO barriers that surrounded the base. Most of the rocks turned up invertebrates like isopods and ants, nothing to write home about. Just as we were beginning to get discouraged, we found something that we’d only seen previously in textbooks. My eyes locked on the pinkish reptile squirming and writing in the blinding midafternoon light. With hesitation, I reached down and grabbed the Zarudny’s Worm Lizard (Diplometopon zarudnyi). It slid through my fingers as I let it go from hand to hand so as not to stress it more than I had to. This little creature was perfectly designed for a subterranean life of digging with its tiny eyes, and shovel shaped face. After we filmed it for posterity with our antique cameras, we let it go back under the rock we found it under. For that moment I was home, at least in my mind.

War or no war, I was enjoying myself with the thrill of discovering new wildlife.

I would often marvel at the nocturnal activity of harvester ants and the absurd abundance of various species geckos we found around our barracks. Observing wildlife at night was easy since most of our missions were conducted after dark. It was my personal mission to share my passion for wildlife with my fellow soldiers. Some part of me needed something else to focus on so I didn’t let my fear overtake me. War can feel like the walls of a very small room closing in on you if you don’t have something positive to focus on. So, instead of letting the negative unknown variables create unwanted anxiety, I herped. I was a combat herper.

My Field Artillery unit was repurposed to do convoys while in Iraq. The Army has a way of putting soldiers where they need them, despite what they had been trained for. The running joke within my unit was that we were now a “transportillery” unit since we didn’t identify as transportation soldiers. I spent half of my deployment as a .50 caliber gunner on a HUMVEE doing convoy security operations, and the other half as a long-haul truck driver. The constant high operational tempo of our convoys allowed me the privilege to see vast swaths of Iraq’s biodiversity. Our mission allowed for a unique opportunity to visit almost all major and minor camps and FOBs (forward operating base) in the countries of Iraq and Kuwait. In one mission we could potentially be in the Arabian Gulf of Kuwait one day and nearing the Northern mountain region of Iraq a few days later. As a naturalist, this was a rare chance that I took full advantage of.

Our missions would range from three or four days, to upwards of three weeks, pending the specific mission and insurgent activity in Iraq. Due to the violence in the region on one memorable convoy, we were forced to spend around three weeks at Al-Taqaddum Air Base (TQ for short) in Western Iraq. Accompanied by my band of lower enlisted lost boys, boredom gave way to bad ideas. We decided to sneak under the barb wire. Those thin strands of concertina wire were the only things protecting us from the dangers of war. We moved just off post to explore a series of blown-up houses on the camp’s periphery. We found that many species of gecko, to include fan footed geckos, had taken up residence in the dilapidated mud huts.

By this time in my deployment, I had cobbled together enough natural history data to begin to have “target species” in my mind that I’d like to find. The fan footed geckos were high on that list. This particular base also had a mini junkyard and debris field that was prime habitat for skinks and even two different species of scorpion. We bided our time exploring junk piles and old buildings at TQ all while the Marines in the neighboring town fought raging battles for Ramadi. I can’t imagine what those heroes must have been experiencing within such a short distance from us. Had we known the danger we could have encountered, I doubt we would have taken such risk. We were three quarters done with our tour and so jaded we almost welcomed death at that point. The respite from boredom was worth the risk. At least that’s what I tell myself now that I’m some 15 years removed from the experience.

I had the sheer luck and goodwill to catch Iraqi bats on two occasions. Once was in a tomb next to the Ziggurat in Ur and once on a wall outside Abu Gharib prison. I studied bats in college prior to deploying, and to find middle eastern bats made me feel somewhat normal for a moment in time. I had to drop out of an environmental biology program at the University of North Carolina at Greensboro to deploy with my Army National Guard unit. Since I was in good standing with the professor, whose research lab I worked in, I got to take a Peterson Bat Detector with me.

This wasn’t a cheap piece of equipment at the time. The bat detector helped me observe the local bats. Bat detectors can hear the ultrasonic sound waves that bats emit for echolocation. Since I could stow the Walkman-sized device in my cargo pocket, I would often take it out when had down time. I would pull out it’s little antenna and scan my surroundings for the tell-tale clicks. I took notes in my rite in the rain journal of what decibels I heard. I tried to decipher what bats may have been around at the time based off of that data. Field guides for the area were almost nonexistent during the early 2000s. The only real information available was a vintage book from the 1919 Mesopotamia expedition and some publications from neighboring countries. Natural history data hadn’t been a high priority in the country for several decades due to constant warfare. Most of what I found while in country was pieced together from safety briefings and the little information I had obtained on my own.

Observing wildlife made being in a combat zone feel almost “normal.”

I was one part naturalist and one part soldier. The standing order was for us NOT to mess with the local wildlife, for safety reasons. Our commander in one breath would give a safety briefing about not interacting with the local flora and fauna, and afterwards would ask me what I had found recently. I would reluctantly give minimal details; in case it was a trap. Once I realized he was genuinely interested, I would open the flood gates on my exploits. The understanding was I could mess with the wildlife so long as I didn’t get hurt. If I got hurt, then I would receive the full weight of punishment. My command knew I was competent with the natural world and it was like a covert mission that only I was equipped to carry out.

It seems I had been preparing for this mission my whole life. As a lifelong North Carolinian, I spent most of my summers cruising back country roads with eyes peeled for various snakes and amphibian species. The week before I left the United States with my unit, I was road cruising the North Carolina sandhills with eyes peeled for pygmy rattlesnakes and scarlet kingsnakes. This skillset came in handy while both scanning my surroundings on convoys for Improvised Explosive Devices (IED’s) as well as keeping an eye out for local fauna. One night I was pulling security around my vehicle, while our convoy was stopped outside of Fallujah, I saw it. A camel spider as big as a baseball scuttled across MSR Tampa (Main Supply Route). Wasting no time, I grabbed an empty Gatorade bottle and chased that solpugid with my M249 squad automatic machine gun bouncing across my back. Carrying a heavy weapon makes chasing desert invertebrates tricky, but I made it work. With my newly acquired nightmare maker now inside the bottle, I went back to pulling security. I kept it the rest of that mission and let it go at our next stop. Camel spiders seemed to achieve a mythology all their own during Operation Iraqi Freedom. We would constantly see forced perspective photographs showing these animals as behemoths, but the reality was they were never more than three to four inches in total length.

The rainy season in Iraq was between November and January the year that I was there. As the gunner in a janky HUMVEE, I got to stand in a turret as sandy rain pelted my face and upper body. The oppressive heat gave way to a bone rattling chill when it rained. After a long-haul mission from Kuwait to Camp Scania in southern Iraq, a typical first rest stop for us, I got out of the cab of my truck and heard a sound I can only describe as heavenly. I heard an animal that immediately made me both homesick and charged with excitement. Toads were calling! In Iraq. My mind was blown. Camp Scania is situated somewhere on the outskirts of the Mesopotamia Marshland and since we were in the rainy season there were handfuls of ditches and small pools full of water. The toads took full advantage of the fleeting periods of suitable habitat and found their way to every puddle and pool that would hold water longer than a few days.

I followed the trill all the way to a pair of toads in amplexus, the mating position of frogs and toads. Once I found the first pair, I started seeing them all around the pool. This moment was one of my fondest memories of my entire deployment. I can’t describe how happy it made me to forget about war for the moment and be a kid in a mud puddle with toads. After making a short video, I said farewell to my anuran pals, and found the transient tent I’d be sleeping in that night. It is often a very fleeting thing during war to feel that kind of elation and I remember not being able to sleep as a lay on my cot that night. For a few hours I felt human. I felt like the old me, the one before wearing a desert combat uniform clad with body armor and automatic weapons. I was that weird kid from North Carolina covered in mud holding toads. That has always been my happy place.

People often are amazed when I explain the beauty of Iraq. I have never seen better sunrises or sunsets than I did from the turret of a gun truck. There were fields upon fields of sunflowers in spring. The desert scrub would even bloom with low lying yellow plants, a favorite for Uromastyx lizards. The Northern part of the country had mountain ranges and at times a breathtaking landscape that is burned into my memory. I had the privilege to see European Bee Eaters perched on concertina wire outside of LSA Anaconda, shore birds and Agama lizards in the Arabian Gulf. I got to witness hedgehogs in Kuwait and in Mosul, Iraq. We saw desert foxes and jackals on every couple of missions while we drove through the night on our missions.

War is a horrible thing, but there are moments of pure short-lived joy if you’re open to them. Not every soldier is a special forces commando kicking in doors and snatching up terrorists. Sometimes individuals like me are sent to war, people who don’t have flashy jobs that make for Hollywood blockbusters. Doing convoys in Iraq both as a gun truck gunner and the driver of an 18-wheeler gave me a perspective that many people did not have. I saw it all. I visited tiny forward outposts and major bases and everything in between. I viewed the country as a scientist, as someone on an expedition to learn about the environment I had been thrust into. It was both foreign and fascinating for me. I tried to view the country with the eyes of a child. I soaked in as much of the environment as I could and those are the moments I will often share. War is hell, but sometimes it can be a hell of a good time, and those are the memories I choose to remember. Those are the stories I’d rather tell. Critter Getter, out.

This article was originally published by REPTILES magazine. Check them out.

If you liked this one, check out these other military articles:

Memories of War; Always Forward

I enlisted in the North Carolina Army National Guard the week before September 11, 2001. I distinctly remember saying to the recruiter that this would be easy money for college since we hadn’t been to war in over a decade. One week later that all changed. The next few years buzzed with wars and rumors of war in my unit, Alpha Battery 5

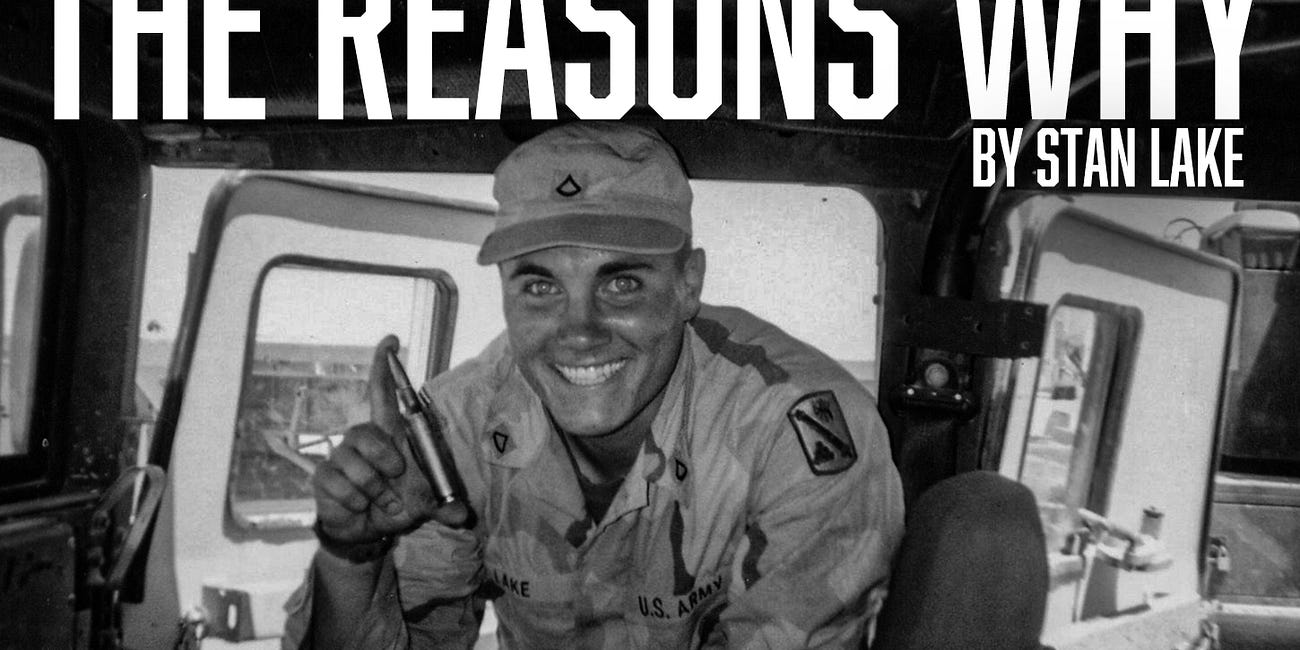

The Reasons Why

The hills crawled with enemy combatants as “Danger Zone” by Kenny Loggins blasted over the headphones on my beat-up cassette player. I sought only to destroy them with speed, surprise, and violence of action. I was a one-man army and took it seriously. My neighborhood was an imaginary combat zone and the local kids were the enemy. Little did I kn…