I enlisted in the North Carolina Army National Guard the week before September 11, 2001. I distinctly remember saying to the recruiter that this would be easy money for college since we hadn’t been to war in over a decade. One week later that all changed. The next few years buzzed with wars and rumors of war in my unit, Alpha Battery 5th-113th Field Artillery Regiment, as we trained relentlessly for a deployment we all knew was on the horizon. In May of 2005, I got the call that changed my life. We were mobilizing. I took my college exams early and traded school books for combat boots.

I took it upon myself during that deployment to be the resident documentarian. I carried a small digital camera in my cargo pocket and a video camera tossed in my rucksack. I shot videos and photos nearly the entire time we were overseas. Our unit was converted from a field artillery unit to a transportation unit and this gave me ample opportunity to see vast swaths of Iraq. We visited nearly every corner of the embattled country and that experience has stuck with me all these years. Nothing compares.

I started the deployment with 2nd platoon, the black sheep, and did most of my training at Camp Atterbury, Indiana with those guys. As soon as we hit boots on the ground in Kuwait, my platoon Sergeant said “Lake, don’t get comfortable, you’re moving to 4th platoon, the gun trucks. You’re going to be a gunner.” That was a shock considering all the training we received suggested that the gunners were the most likely to sustain casualties during convoys. Great! Although I was frightened, I was also excited about the new mission. I took great pride in being a part of the misfit gun truck crew. We got some great training at the Udairi Training Range in Kuwait and my confidence began to build.

On my first mission in Iraq, I did what’s called a right seat ride with the Iowa National Guard unit we were replacing. This was so they could show us the routes and what to expect in country. The Iowa guys I rode with on that mission brought a bag of soccer balls for the Iraqi kids. A school in their hometown donated them for the children in an attempt to win hearts and minds. As the gunner, I had the best vantage to throw the balls to the kids. That moment created a significant amount of dissonance for me. I was both scared to death of being in a combat zone while simultaneously having a moment of pure confusing joy. To see the happiness on the faces of these children juxtaposed against the war-torn landscape was emotionally jarring.

The children were mostly barefoot and in colorful, threadbare clothing. They were all smiling as big as can be. The moment was broken as we rolled away when the beautiful Iraqi girl who caught the soccer ball was chased down and beaten mercilessly with sticks and fists by the surrounding boys so they could get the ball from her.

I immediately went from a sacred moment of shared joy to complete rage. I was powerless to do a thing about it. The convoy rolled away with me as the rear convoy gunner. All I could do was watch the shocking melee as we ambled down the road in hand me down equipment to complete our mission. This scene lingers in my brain all these years later as if it were yesterday. War is dissonant, war is hell.

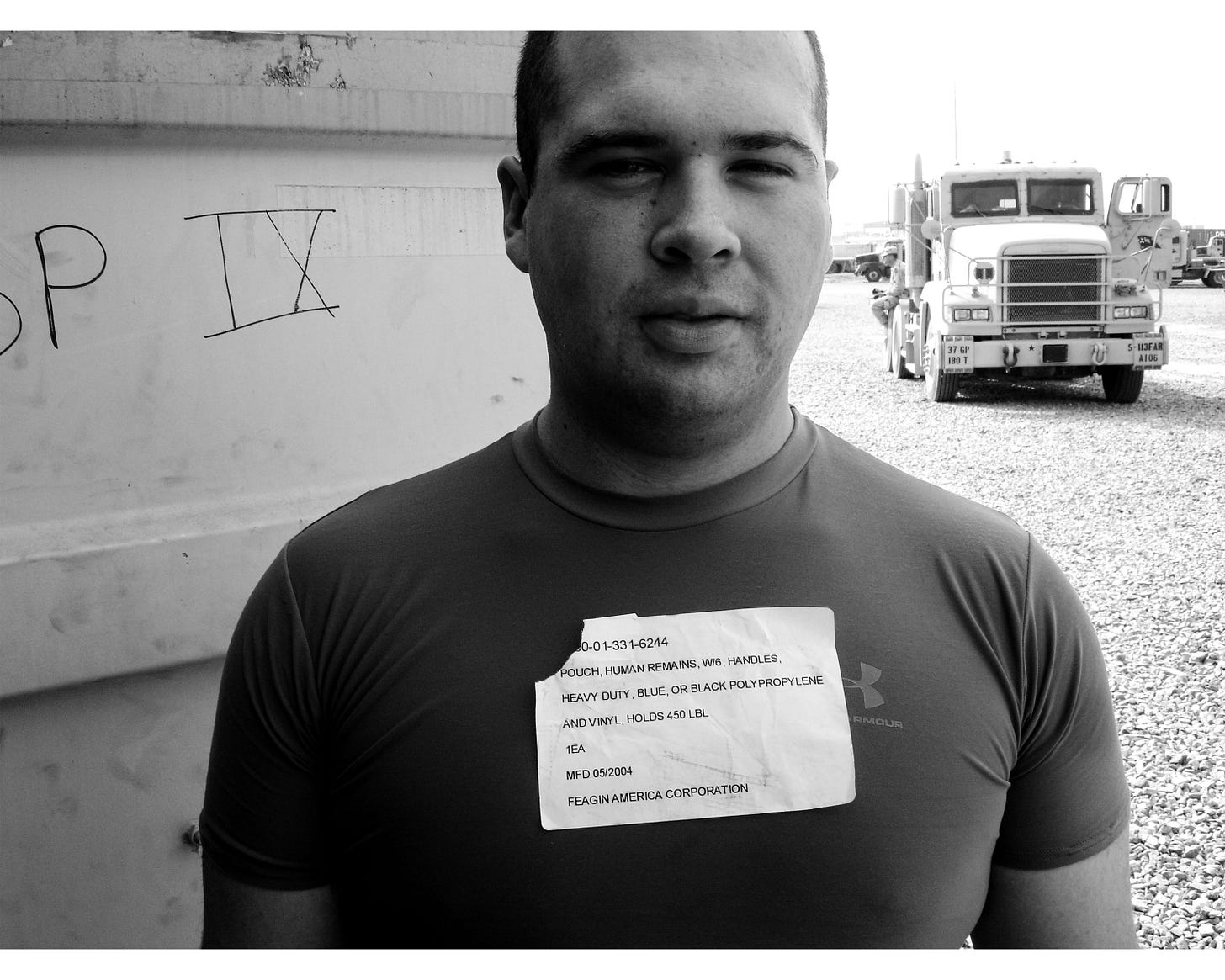

As the operation tempo increased, I became desensitized to the landscape around me and the children seemed to be the only things that could occasionally snap me back out of it. “We decided at a certain point that we were already dead and it was useless to fight it,” said Jacob Young, a fellow gun truck operator, when asked about a picture I took of him with a label for a body bag stuck to his chest. We were just kids having to deal with the very real fact that we may not be as invincible as we previously thought. Every day could be our last and at a point, we all just stopped caring and started making jokes. Amazingly, we were all able to come home in one piece, which is a rarity given the mission we had.

War is a funny thing. It can take a group of people who have absolutely nothing in common and make them brothers. There is something about shared trauma that can solidify a bond sometimes deeper than blood. This is a family forged in the fires of combat. Although you may be from different socioeconomic backgrounds, religions, races, and et cetera, you are bonded for life.

To say Shawn Patterson and I were an odd couple at first, would be an understatement. I would not go so far as to say we hated each other before we were forced to work together in that gun truck, but I will say there was a strong dislike, at least on the surface, at first. Shawn was a Newport smoking, “wife-beater” tank top, and basketball shorts wearing hip hop aficionado and I was a black T-shirt and jeans, hardcore kid. The two couldn’t be further apart, or so I thought. Where Shawn and I differed on style, ideology, and musical taste, we bonded over the unique situation inside that gun truck.

We learned very quickly that to survive this deployment, we would have to look out for each other. We were all scared and didn’t know what to expect. Shawn and I quickly realized we were on our own and we had to have each other’s backs. Shortly after our missions began, our Sergeant was transferred to another section.

His replacement was one of the best combat leaders one could ever ask for, Staff Sergeant Silver. This man was as hard as pterodactyl lips and the true essence of a wartime leader. The mission we went on with SSG Silver was one of the best we’d had to that point and we felt like we were in capable hands with a true leader.

Shawn and I would stick together once our gun truck platoon disbanded due to “safety concerns” (aka lack of legitimate armor) midway through our tour. We both assimilated into the same squad in 1st platoon, since we did the bulk of our convoy security missions with that platoon, it seemed to be a good fit. This forged a friendship that has spanned almost two decades now and although we don’t speak often, when we do it’s like no time has been lost. Years after that deployment, I got to be the best man at his wedding. All because we shared a cramped Humvee with “armor” we bolted on in a desert far, far away when we were both young and dumb.

When we came home from that deployment, I burned my war journals. I only wanted to remember the things I felt I could never forget. I didn’t want to live in that place anymore. Reflection can be a good and healthy thing for veterans, but often we can get stuck in those cycles of “the good ole days.” We must remember to not let the past define us. To quote the Danish philosopher Soren Kierkegaard, “Life can only be understood backwards; but it must be lived forwards.” Let’s remember that our best days aren’t yesterday and to take the lessons we learned in combat and move forward. Always forward.

CALL YOUR BUDDIES!

Originally published in the “Tarheel Guardsman” print magazine for the North Carolina National Guard Association.

Great story and tremendous photos. But man, that picture of the kid headbutting the ball?! That's unreal. Should be hanging in a fucking gallery somewhere.