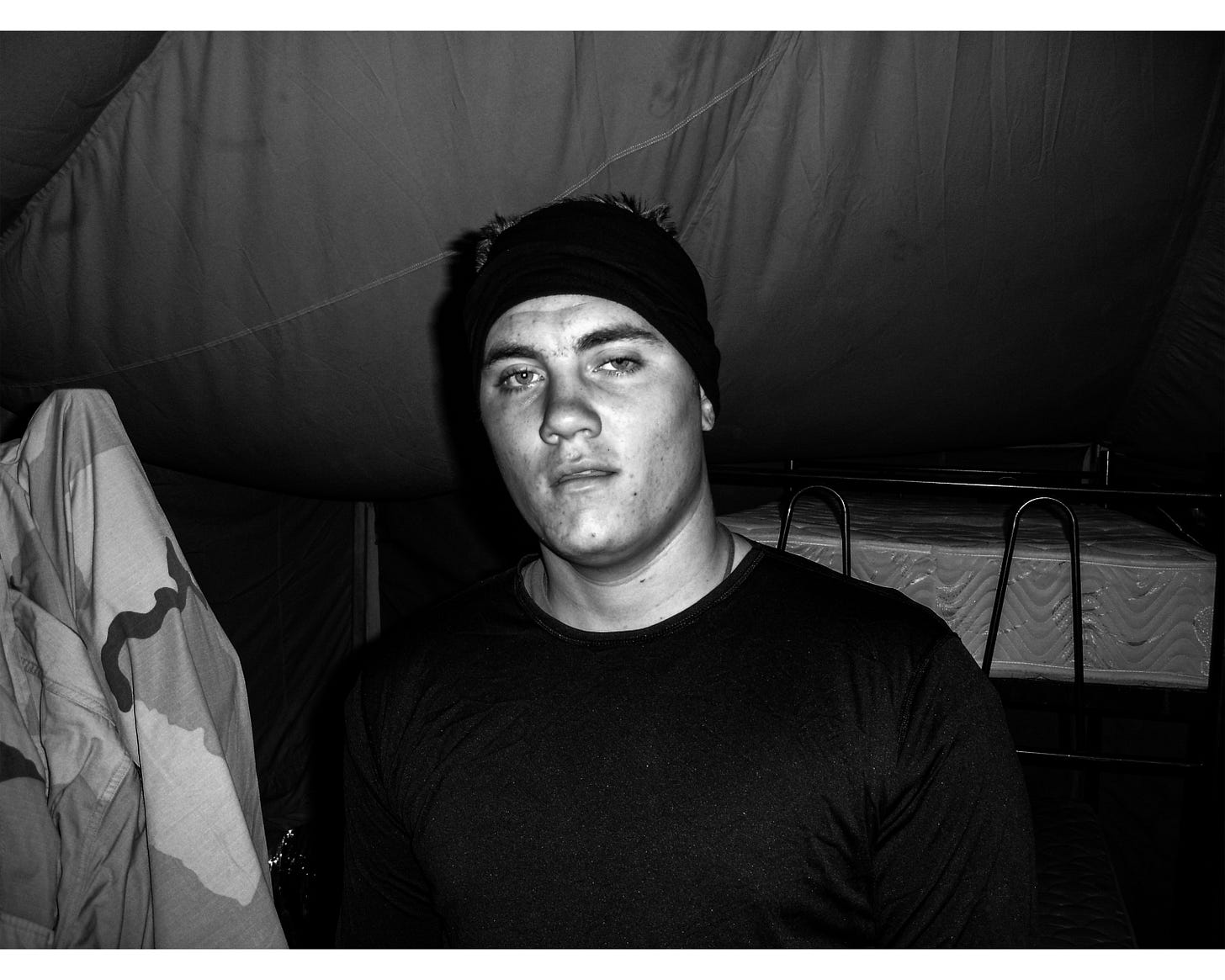

Sometimes when I think of the war, my war, I see all the things I was way back then. A lump develops in my throat. I was young, idealistic, and on a mission to save the world and protect our freedom. At least that’s what I thought at the time. I never lost any freedoms I didn’t volunteer for, and those poor Iraqis had no qualms with me. I fought for a God I didn’t believe in at the time, and a country that didn’t care about me, I suppose. God bless the troops, or something.

Today marks eighteen years since I left home to go to Iraq and seventeen years plus or minus since I came home. You may notice the tone of this piece skews a tad bit negative. That’s the point. I’m tired of always having to sanitize experiences for people that have never left the safety of their hometowns. That may sound harsh, and for that I apologize. This isn’t an indictment to anyone in particular, just an expression of the reality of war for me. No one forced me to serve and I surely didn’t expect to go to war, but I did. Sometimes it feels like I never actually left, or that a part of me died over there; the innocent part.

Every so often those old bad feelings rise to the surface. Truthfully, I just get tired of carrying it alone sometimes. The war ends for you when you click the x in the corner of this web page, but for many of us there is no x. The cycle goes on and on. This isn’t an attempt to get anyone to thank me for my service, or even something to make you feel sorry for combat veterans; it’s simply a way for me to communicate the realities in which many of us live, if we are being honest. Veterans are portrayed as broken all too often in the news and that is not what I’m trying to convey either. We aren’t victims, we volunteered.

I also want to make it very clear that although war is traumatic in its very nature, my tour wasn’t overtly violent like so many Iraq and Afghanistan veterans’ experiences were. I’m not delusional in thinking my war was worse than anyone else’s, it was just my experience and the only one I have to go on. That said, what I did experience was enough for me. Even though I rode behind the .50 Cal machine gun in the turret of a gun truck half of my deployment, don’t let it fool you, I never fired a shot in anger or defense. The violence loomed like dark storm clouds on the horizon and you never knew when lightening would strike. I lived in that perpetual fear day in and day out, and sometimes the fear of something occurring is worse than if it actually does.

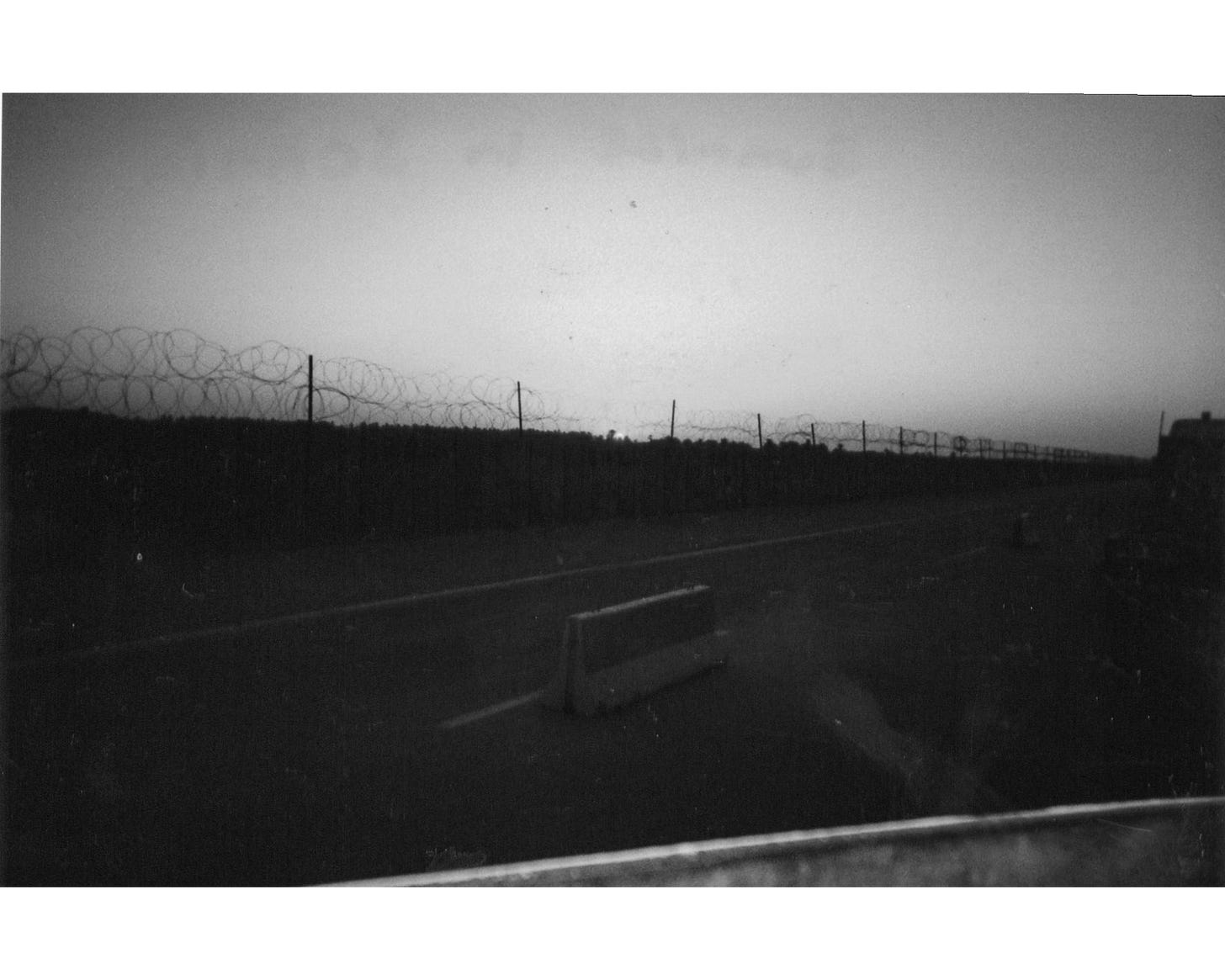

This isn’t to say things didn’t happen or even that bullets didn’t fly in my general direction, they did. Hell, the title picture for this article was of a mine field we drove through, and the IED (Improvised Explosive Device) we almost hit, and later had detonated by EOD (Explosive Ordinance Disposal). I just wasn’t one of the door kickers or hard chargers like so many of my peers. My fear as I recount my experiences is that another veteran, one much more qualified than I am, will discount my voice. We are known to eat our own. So, I want to lay bare that this is my experience and some had it better, some had it worse, but in the end we all carry invisible wounds from that war. Our war.

I can still feel the crunchy grains of sand between my teeth. The oppressive oven-like heat, with a wind reminiscent of a hair drier on high, still blasts my memory. The burning, the coughing, always something on fire. The smell. God the smells. The fear. The apathy. The hopelessness. It all still lives inside of me. All it takes is a shift in the wind for me to remember the best of bad times. The worst of good times. It’s as if dissonance floats on the summer breeze. I often think I’ve gotten over those old days, and then out of nowhere something triggers a feeling I just can’t bury anymore. I wipe my eyes and punch the steering wheel, and remind myself to suck it up and drive on. Just like we were trained to do.

I can’t recall specific details from my wedding day, or other monumental milestones in the last eighteen odd years. I can still remember how Iraq smelled. I remember how my uniform felt in the dry heat, and how it clung to me in the humidity of the Arabian Gulf in Kuwait. I remember how it felt to drive bomb littered routes hauling shit no one needed, to places time forgot. Memories are funny like that. I don’t want to carry the weight of it anymore. I’m tired of telling this story, and yet it’s seared in my brain like a cattle brand. Every summer I get into a funk for whatever reason, I can only assume that mentally I associate the heat with another time and place. It doesn’t take much.

People far better than me did things far greater than I ever could, and yet, I keep writing stories. The same story. Recycled and re-edited from other angles. From other perspectives or inferences. But the story is the same. Scared kid from a small town goes off to war, comes home anxious, lost, and confused. Even though I likely left that way, it seems more poetic to just blame it all on the war, my war. I think admitting that I sometimes struggle with it isn’t an admission of weakness, it’s a projection of strength. I own it. I struggle through, and so many times I write it down. I fear that it makes my family uncomfortable but I also pray they understand these rhythms by now and know it’s just my process. I’m okay. Mostly.

What is it about soldiers that makes us desperately want to tell our story, and at the same time, retreat within ourselves and not say a word. We live somewhere between combat chroniclers, gregariously boasting of our exploits, and hermits avoiding conversations. We hold on to our stories as if it’s all we will ever do. For some of us, many of us, it was the biggest thing we ever did. I pray I’m not one of those guys that can’t escape the war, but here I am writing this story, again and again. I’m trying to make sense of it all. One day I’ll forget the details and perhaps the feelings attached to that time in the sand. Part of me never wants to forget. It’s like a pain you have to occasionally press just to feel something, anything, just to feel alive again. Every so often I just want to remember I did something of note, something I was called to do that was worth the mental anguish it caused. Does that make me weak? Maybe. I’m ok with owning it though. I’ve got nothing to prove to anyone anymore.

The war sometimes seems as if it was the only worthwhile thing I will ever do. And the cycle repeats. Share a story, retreat back behind those lines of uncomfortable memories. That old enemy of restful nights dances like a specter in my brain keeping me from sleep. Tell them about the good times. Withhold that part about blood on the pavement. If it bleeds it leads, so they say, but you just want to protect them from those things you saw, and did. You tell a story about catching a hedgehog on a mission in Mosul. You never tell your mother about the recently executed body you saw on the side of the road while you were stuck on that bridge in Baghdad, or the fear and helplessness you felt. You do a little dance on camera, smile, wave and pretend it’s all okay. Maybe one day it will all be okay. Maybe you’ll stop seeing his face when you close your eyes at night. He wasn’t the only one, but he stands out for whatever reason, and so I write. Maybe I can edit him out of my mind. I still wonder who killed him.

No one wants to hear about the children you saw screaming with bloody bandages and burns waiting for a medic to redress their wounds on your way to the “Haji Mart.”That story may make us look like the aggressor, and not the valiant liberators we claim to be, even though most of the time we were. Tell them the story about giving beggar children pens and paper so they can go to school. One of the few times you saw the people as more than just the enemy, you saw their humanity. That’s a safer story with a happy ending. That one makes people smile. That one also makes me cry. I still haven’t unpacked why those children always break me when I think back. I guess it has to do with the fact that they didn’t choose to grow up in a war and kids represent the innocence, the best of us. Don’t tell them about sobbing into your pillow on Christmas because the pay-phones in the call center kept dropping your calls, your only lifeline to the real world. That doesn’t make flags wave. Patriots don’t cry.

Maybe things like this are why it’s so hard for us to tell our stories. People want to support the troops until they have to help us carry the weight of our experiences. The GWOT (Global War on Terror) generation went from combat to “normal life” within a matter of days, and were somehow expected to play nice and act like nothing happened. Other generations had long transitional periods just on the basis of the time it took to get them back home. They had time to process the war and decompress to some degree. We had to flip a switch from one day to the next. Whatever you do, don’t talk about the bad stuff. That dissonance you carry is hard to tune out. A pride in one’s country, coupled with a confusion about mission and purpose definitely stirs up static in your brain. You can disagree with the war and be proud of your service in it, I give you permission. I have to constantly give myself that same authorization. I love this country, but I often disagree with our zeal for bloodshed. Maybe one day we will take the higher road.

God bless America. Cue the Toby Keith or Lee Greenwood or whichever war profiteer stokes the embers of conflict from the safety of never serving. You did it soldier, thank you for your service. Please don’t make us sad. Please don’t make us confront the cost of war. We are American patriots. We sent you to get the bad guys. Light some fireworks, salute the flag, and shut up. You are home. The war is over. Now forget all about it, we don’t want to hear about it anymore.

In an effort not to end on a complete sour note let me illustrate a few positives from that experience to round this out. Although war is hell, at times it’s a hell of a good time as I’ve said many times. I made lifelong friends who became brothers, not by blood but by the trials forged in the fire of war. I learned that at some level, when tested, I could rise to the occasion. I learned I wasn’t a quitter and could do things even when I was scared spitless. Most of all I learned that it’s ok to struggle, what’s not ok is giving up. So many veterans from my generation are taking their lives and likely it stems from constantly carrying the load alone. This article may make you uncomfortable but which would you prefer, a sad story from a living veteran, or a sad story from those left behind? Thank you for giving me voice and letting me share my burden with you. I pray other veterans can do the same so we can heal collectively, and perhaps we can become the next greatest generation. This is how we can start to close the gap between those who served and those who have not, and begin to speak a common language of healing.

If you’re interested in a documentary about my time in Iraq, check out “Hammer Down.” This documentary was shot in 2015 and released in 2016 on the 10 year anniversary of our homecoming. We were given a small grant from the NC Humanities Council to tell our stories and it later became part of the NC high school curriculum for that school year for history teachers, at least in Wilkes County, North Carolina. It’s a mix of footage we shot in 2005/6 while deployed with interviews ten years later. The documentary is a roller coaster of highs and lows but focuses mainly on the things we did to stay sane while deployed, like shenanigans between missions.