Did you ever play that game when you were a kid that required you to pretend the floor was made of lava? The couches and other furniture were little islands impervious to being consumed by said lava, offering floating oases among the magma flow. Now imagine being grown and having a similar situation while out observing wildlife. Substitute lava for deadly pit vipers, and the couch for loose crumbling boulders. Now that I have painted that beautiful picture, welcome to one of my misadventures with some spicy fauna.

After a late-night phone call with a good friend and snake mentor of mine, I got invited to go observe some timber rattlesnake dens in an area I hadn’t been before. I jumped at the chance. My friend Zach has been showing me the wonders of the serpent world for the last twenty years or so. I met him while in high school when he came and did a presentation on venomous snakes for our natural resources class. It was one of those presentations that stuck in my mind since I was already quite passionate about snakes. A few years later, I linked up with Zach again at a reptile show and he gave me his contact info. We began a friendship that has been priceless to me.

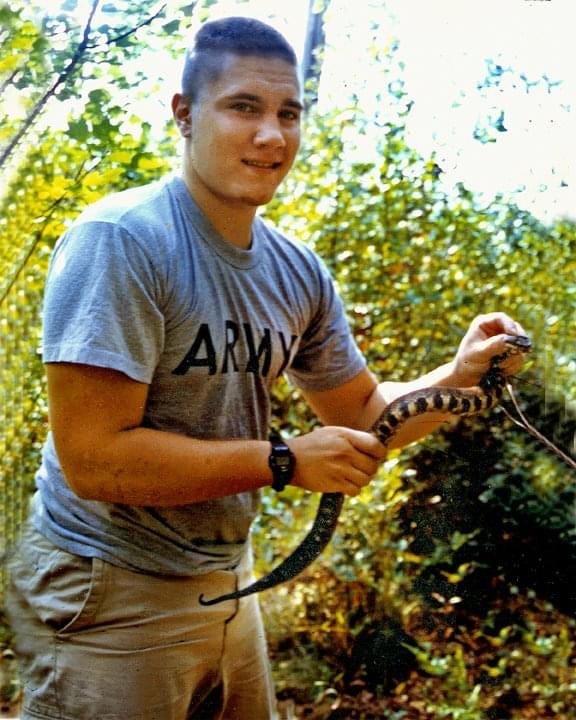

I have learned so much from his hands-on experience, and seen so many things in nature that I wouldn’t have had the chance without him. I held my first venomous snake (a large cottonmouth) with him behind the camera when I was eighteen and fresh out of basic training. I saw my first pygmy rattlesnake with him in the sandhills of North Carolina, and countless other snake firsts. So, going to a new rattlesnake den with him was a no brainer for me. Little did I know that this experience would be one for the record books. I truly had no idea what I was literally walking into. My previous experiences with timber rattlesnake dens were small rocky outcrops in the Uwharrie National Forest, and typically only seeing less than five adult rattlesnakes basking.

This particular journey began rather early for me as I waited at a local Starbucks for him to pick me up since I live at the approximate halfway point to our destination. This area was North and West from where we normally hunt for snakes. The terrain was steeper and craggier, and tended to be more montane than the piedmont hills I’m used to. After a dizzying ride through curves and back roads, I stumbled out of the car wanting to vomit from motion sickness. We had arrived. I ambled up the steep incline to our destination, taking many rest breaks along the way. Partially because I’m out of shape and partially because the mountain was so steep you almost had to climb and scramble upward. I could touch the mountain as I lumbered upward. Had it been any steeper, ropes might have been necessary, just to give you an idea.

Zach scrambled up the mountain with the ease of a mountain goat, leaving me gasping with my hands on my knees every few feet. Once I finally reached the top, where my friend had been patiently waiting, I saw what looked like massive piles of rubble. This ridgeline housed hundreds, maybe thousands of Timber Rattlesnakes (Crotalus horridus) all hidden among the litany of rocks strewn about. The piles of stones ranged in size from gravel chunks to car sized boulders. It looked like dump trucks had abandoned miles of crumbly boulders across the ridge. Weathering and erosion over a millennium created this unique, and seemingly hostile habitat. This ragged ecosystem proved to be the perfect winter resting place for cold blooded ophidians. Having only been to rattlesnake dens in the piedmont of North Carolina, this area’s topography was like an alien landscape to me.

The boulders, no matter how big or small, weren’t exactly stable to walk on. You really couldn’t tell whether the large rock you were standing on would support your weight, or would slide and roll down the steep incline promoting a rockslide. It was quite deceptive, and each step was calculated. Sometimes, even when you were cautious, the rocks would still slide. The terrifying part about this, aside from falling to an untimely death and being crushed by rocks, was that under most rocks contained a hiding viper or two.

I stepped on several moving boulders only to be shaken to my core by the telltale sound of an alarmed rattlesnake. The rising hiss of the rattles seemed to come from all around me, even from inside of me. The sound was everywhere! There were a few moments where the rock would shift, the snakes would rattle and I had to frantically deduce where the sound was coming from. Was the sound coming from beneath me, beside me, is the snake poised to strike right where I’m about to put my hands/feet? Nothing makes you pay attention to your footfalls more than the possibility of a painful necrotic bite.

After we had seen and heard approximately 25 rattlesnakes, which according to Zach was a “bad” day, I began to get quite nervous about this adventure. As I was looking up the hill at Zach, and seeing the rattlesnakes coiled under the weathered rocks above me, my cooler sized boulder began to shift without warning. As the rock slid downhill, I lost my balance and with a twist I fell face first down the hill crashing chest first, then knees then hands into a pile of boulders. I am whatever the opposite of graceful is.

I didn’t even give my body a chance to register to pain before I was up, catlike, balancing on new boulders after my fall. My heart was pounding, my knees were shaking and I was praying, “Lord please don’t let me have landed on a viper.” Once I was able to catch my breath and dust myself off, I saw that I only sustained a few scratches and bruises. Thankfully there weren’t any snakes ready to defend themselves, and in my eyes, it was truly a miracle that I didn’t get hurt worse than I did.

After the shock and adrenaline wore off a bit, I began to feel the soreness in my body. I was just happy to be alive. There was no venom coursing through my veins, and I had no broken bones. I should have been hurt way worse than I was and again, to me that was a miracle. I didn’t want anything that’d make me linger in the danger zone longer than necessary. My mission now shifted from a naturalist observing wildlife, to a clumsy survivor trying to get back to safety before the storm, or snakes, hit. I scooted on my butt down the steep grade, passing piles of black bear poop as I went. My mind was racing as I was scooting downhill. “How many things want to kill me up here?” I thought.

Rattlesnakes will typically congregate in the fall at rocky outcroppings to use as dens for the winter. They will often communally hibernate in these areas and utilize this seemingly perfect spot together twice a year. You will see them out en mass in late fall as they are coming from miles away to find shelter, and again in spring as they emerge from their wintry sleep. Outside of breeding and denning, they live a predominately solitary life.

Although I ran the very real risk of being greeted by an angry bite from a pit viper this trip, I couldn’t have blamed the snake. I was in his territory, his house, and invading his space. I imagine I’d react the same way if an unwanted visitor walked all over my house. Even though the risk was great, seeing these amazingly beautiful animals in their natural habit trumped any threat involved. At least that’s what I told myself once I was safely back on level ground getting back into the truck. I sat down in the passenger seat and crashed. I woke up as Zach was pulling into the Starbucks that we’d met at earlier that morning. I slept the whole way back.

Rattlesnakes are a vital part of the ecosystem and their removal of would cause a ripple effect ecologically that would be catastrophic. They benefit humans by eating rats and mice that carry diseases like Lyme’s disease. They also serve humanity by other means. Their venom, while toxic in its natural state, shows promise for its use in life saving medicines. Enzymes and proteins derived from the venom of pit vipers has been used to treat issues ranging from hypertension, heart disease renal disease in diabetes patients, stroke, and even as potential cures for some cancers. They are one of natures systems for checks and balances, and if we can truly see their beauty and try to understand them, then perhaps our children will have the benefit of seeing these amazing creatures in the wild. We shouldn’t villainize things we don’t understand. Snakes are great, just keep a safe distance!

I can just see you attempting to traverse those same rocks today, of course, I'm standing down at the car with binoculars at my age!